Merck Turns to Tumor-Killing Viruses in Immune Cancer Treatment

Scientists have tried to muster viruses to hunt and kill tumors for almost 70 years, with limited success. That may be changing.

Now, microbes are playing an important role in an emerging branch of cancer immunotherapy that’s attracting some of the world’s biggest drugmakers. Merck announced plans to buy Australia’s Viralytics Ltd. last week to gain an experimental cold virus-based treatment that may bolster the utility of Keytruda, its blockbuster cancer medicine.

The A$502 million ($390 million) deal underscores the importance of research into so-called oncolytic viruses, which work by infecting and destroying tumor cells as well as stimulating an immune response. The approach is garnering growing interest from pharmaceutical companies because of the possibility of coupling these viruses with a new generation of medicines, called checkpoint inhibitors, that counter a strategy cancer cells use to escape detection.

Read More: Checkpoint Inhibitors’ $42 Billion Peak Opportunity

“There’s interest from Big Pharma in this field,” said Malcolm McColl, managing director of Viralytics, which agreed to be bought by Merck for A$1.75 a share in cash -- or almost three times the stock’s previous closing price of 62.5 Australian cents. “There is a growing view that oncolytic viruses could have potential in making checkpoint inhibitors, like Keytruda and other drugs, work better.”

With the number of new cancer cases predicted to increase by about 70 percent globally over the next two decades, scientists are focusing on ways to improve treatments, especially for malignancies for which standard chemotherapy and radiation provide little benefit.

Often in those cases, the tumor harbors mutations that make it invisible to the patient’s immune system, rendering it a so-called “cold cancer.” The challenge is to increase the level of immune infiltration, turning it “hot.”

Hot and Cold

“Oncolytic viruses are at the top of the list of promising new strategies to turn ‘cold’ tumors ‘hot,’ and to get to the immune system to learn what the tumor looks like and to attack it both locally and distantly,” said Anthony Joshua, head of the department of medical oncology at the Kinghorn Cancer Center in Sydney.

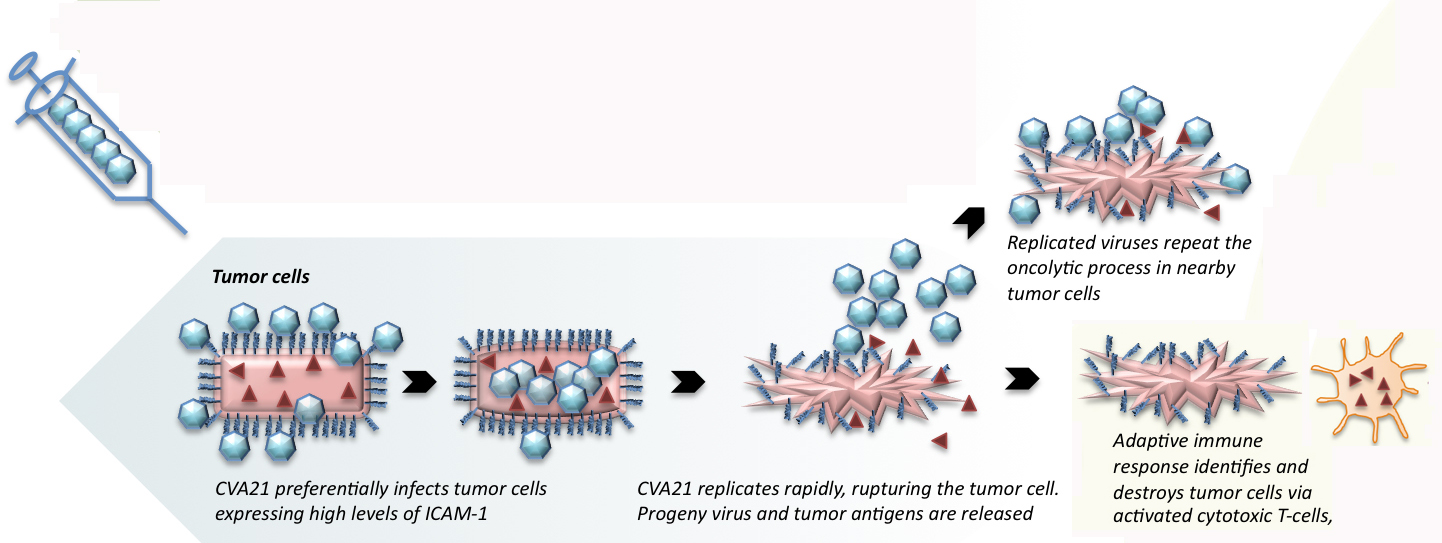

Viralytics’s most-advanced treatment, Cavatak, is based on common-cold virus Coxsackievirus A21, which seeks out and latches itself to a protein prominent on the surface of many cancer cells. Once attached, the virus hijacks the cancer cell’s genetic machinery to make more copies of itself, causing the cell to explode in a cloud of new viral particles, a process known as lysis. Viral progeny can then spread and replicate this cycle of destruction.

Cavatak, which completed mid-stage studies in melanoma patients, is also being investigated as a treatment for lung and bladder cancers, including in combination with Merck’s Keytruda, and Yervoy, a checkpoint inhibitor developed by Bristol-Myers Squibb Co.

Case studies and small trials using various, crudely prepared viruses for cancer therapy were conducted throughout the 20th century, but it wasn’t until the 1990s that genetic engineering tools were used to enhance their oncolytic potential, Antonio Chiocca and colleagues at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston wrote in a June review of the topic.

Amgen Acquisition

A major milestone came in 2015, when a tweaked version of the HSV-1 cold-sore virus injected into tumors became the first oncolytic immunotherapy to demonstrate therapeutic benefit against melanoma in a late-stage trial. The drug, created by BioVex Inc. -- which Amgen Inc. bought in 2011 for as much as $1 billion -- was the first of its kind to gain regulatory approval in the U.S. in 2015 and Europe in 2016.

“I think there is going to be a resurgence of the oncolytic virus field,” said Antoni Ribas, a professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, who has worked in cancer immunotherapy for 20 years. Enthusiasm for the approach has been bolstered by the potential of viruses to amplify the activity of the checkpoint inhibitors, he said, adding that other strategies for stimulating the immune response also look promising.

Besides Cavatak, other oncolytic viruses are closing in on drug approval in North America and Europe, Tomoki Todo and colleagues at the University of Tokyo’s Institute of Medical Science wrote in a 2016 review paper. These included:

- Pexa-Vec, based on the smallpox vaccine virus, and under development by SillaJen Inc. and studied in patients with liver and breast cancer, sarcoma, and in combination with checkpoint inhibitors for colorectal cancer.

- CG0070, based on a modified common cold adenovirus; being developed by closely held Cold Genesys Inc. and studied in patients with bladder cancer as well as with checkpoint modulators for other solid tumors.

- DS-1647, or G47Δ, based on a mutated HSV-1 virus; being co-developed by Daiichi Sankyo Co. and designated in July as an orphan drug for the treatment of malignant glioma by Japan’s health ministry.

- Reolysin, a respiratory enteric orphan virus; being developed by Oncolytics Biotech Inc. and studied in breast cancer patients.

Brain Cancer

Transgene SA began treating patients with glioblastoma, a form of brain cancer, using TG6002, a novel oncolytic based on the smallpox vaccine virus, the French company said in October. Japan’s Takara Bio Inc. said in December it would start testing its HF10 virus in combination with Bristol-Myers Squibb’s checkpoint inhibitor Opdivo for melanoma after it began studying it in pancreatic cancer patients.

Closely held DNAtrix Inc. is also tackling glioblastoma with its DNX-2401, based on a common-cold virus, in combination with Merck’s Keytruda, while Genelux Corp. is also testing tweaked smallpox vaccine virus against gynecological cancers.

Companies developing promising oncolytic viruses will be attractive to cancer-drug makers, said Rajiv Khanna, a senior scientist at the QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute in Brisbane, Australia, who has worked in tumor immunology for more than 20 years. For much of that time, major pharmaceutical companies weren’t interested in oncolytic viruses, he said.

“But suddenly they have woken up and seen these results,” said Khanna, whose lab is studying ways of killing cancers that are caused by viruses. “I was impressed that Merck would pay that much money for a company, but their results are quite encouraging, so it makes sense.”

Source:https://www.bloombergquint.com/technology/2018/03/01/merck-turns-to-tumor-killing-viruses-in-immune-cancer-treatment

Comments

Post a Comment